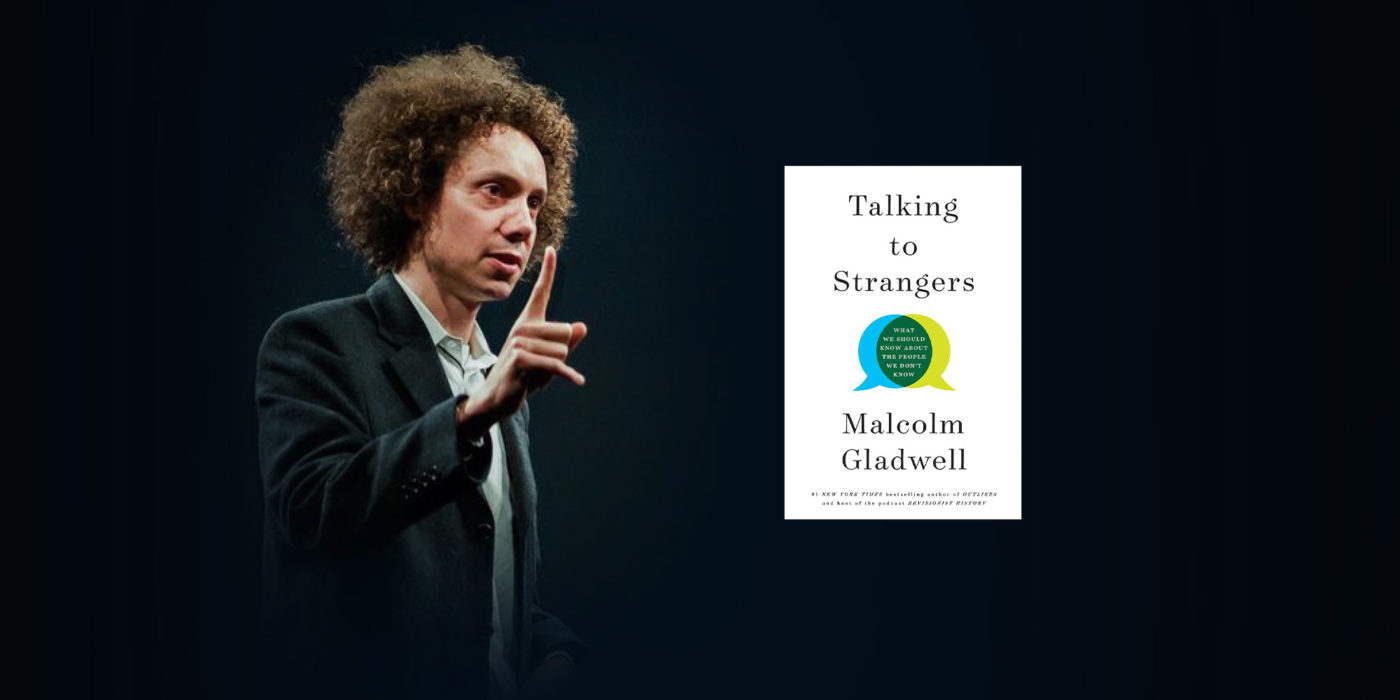

For millennia, we were born, raised, and died within the same community, alongside others who were just like us. Our language, facial expressions, and behaviour followed a predictable pattern based on what we saw around us. As a result, our brains are hardwired to expect others to behave in specific and predictable ways, based on how we believe we would behave. However, due to human migration patterns and the rise of the Internet, we are more connected than ever with those who are different from us. “Talking to Strangers: What We Should Know About The People We Don’t Know”, Malcolm Gladwell’s most recent curiosity-driven book, explains why we are inept at understanding each other and why our own cognitive processes doom our interactions from the start.

Gladwell is the author of five New York Times bestsellers including “Tipping Point,” “Outliers,” and “David and Goliath.” Since the release of “Tipping Point” in 2000, he has become a pop-culture icon known for asking readers to think deeply about how we operate in the world around us. “Talking to Strangers” follows his signature formula using well-researched anecdotes to connect the reader to his theories, diving deep into his examples before pulling the reader back to the larger thesis.

The story of Sandra Bland was the starting point of the book for Gladwell. Bland was an African American woman on her way from Illinois to Texas for a job interview. After a traffic stop went awry, she was taken into police custody and found hanged in a jail cell three days later. While many distilled the exchange to prejudice and incompetence, Gladwell was curious about what really contributes to these catastrophic interactions. He writes, “We put aside these controversies after a decent interval and move on to other things. I don’t want to move on to other things.”

Similarly, he explores “the idea that behaviours are linked to very specific circumstances and conditions” or “coupled”. For example, crime research clearly shows that incidents are concentrated on a tiny number of streets. Suicide rates are also closely tied to location, as evidenced by the steep drop in suicides in San Francisco after a protective barrier was constructed on the Golden Gate Bridge. Experts assumed that those who wanted to take their life would find another way, but that simply wasn’t the case.

Gladwell also introduces concepts like “default to truth”, which explains that we automatically default to believing that someone else is telling us the truth, even when faced with evidence to the contrary. It would be too great a burden to imagine everyone is always lying to us. So we choose to believe they are always telling the truth—until, of course, there is so much evidence to the contrary that we have no choice but to see them as deceitful. Gladwell summarizes, “You believe someone not because you have no doubt about them. Belief is not the absence of doubt. You believe someone because you don’t have enough doubts about them.”

In his opinion, this is why Amanda Knox was suspected of murdering her roommate in Italy despite a lack of evidence. Her behaviours didn’t match what was expected of her: instead of being sad and withdrawn, she was loud and angry. “Matched people conform with our expectations,” he says. “The mismatched are confusing and unpredictable.”

Amanda’s story and other vignettes are extremely rich and detailed, so much so that you can get lost in the details before once again realizing they are part of a larger point he’s working to prove.

Gladwell showcases many of the challenges we face as we work to understand each other. This “conversation starter” of a book is certainly designed to equip the reader with both the facts and the resolve to engage more thoughtfully with others. I only hope that some of the conversations are with strangers, that they occur with the “caution and humility” that he encourages, and that they help to break down the natural barriers that cause us to misunderstand each other. We’ll all be better for it.